Managing dependencies well is an essential part of writing solid code. C++ supports two powerful methods of abstraction: object-oriented programming and generic programming. Both of these are fundamentally tools to help manage dependencies, and therefore manage complexity. It’s telling that all of the common OO/generic buzzwords—including encapsulation, polymorphism, and type independence—along with most design patterns, are really about describing ways to manage complexity within a software system by managing the code’s interdependencies.

When we talk about dependencies, we usually think of run-time dependencies like class interactions. In this Item, we will focus instead on how to analyze and manage compile-time dependencies. As a first step, try to identify (and root out) unnecessary headers.

Problem

JG Question

1. For a function or a class, what is the difference between a forward declaration and a definition?

Guru Question

2. Many programmers habitually #include many more headers than necessary. Unfortunately, doing so can seriously degrade build times, especially when a popular header file includes too many other headers.

In the following header file, what #include directives could be immediately removed without ill effect? You may not make any changes other than removing or rewriting (including replacing) #include directives. Note that the comments are important.

// x.h: original header

//

#include <iostream>

#include <ostream>

#include <list>

// None of A, B, C, D or E are templates.

// Only A and C have virtual functions.

#include "a.h" // class A

#include "b.h" // class B

#include "c.h" // class C

#include "d.h" // class D

#include "e.h" // class E

class X : public A, private B {

public:

X( const C& );

B f( int, char* );

C f( int, C );

C& g( B );

E h( E );

virtual std::ostream& print( std::ostream& ) const;

private:

std::list<C> clist;

D d_;

};

std::ostream& operator<<( std::ostream& os, const X& x ) {

return x.print(os);

}

Solution

1. For a function or class, what is the difference between a forward declaration and a definition?

A forward declaration of a (possibly templated) function or class simply introduces a name. For example:

class widget; // "widget" names a class

widget* p; // ok: allocates sizeof(*) space typed as widget*

widget w; // error: wait, what? how big is that? does it have a

// default constructor?

Again, a forward declaration only introduces a name. It lets you do things that require only the name, such as declaring a pointer to it—all pointers to objects are the same size and have the same set of operations you can perform on them, and ditto for pointers to nonmember functions, so the name is all you need to make a strongly-typed and fully-usable variable that’s a pointer to class or pointer to function.

What a class forward declaration does not do is tell you anything about what you can do with the type itself, such as what constructors or member functions it has or how big it is if you want to allocate space for one. If you try to create a widget w; with only the above code, you’ll get a compile-time error because widget has no definition yet and so the compiler can’t know how much space to allocate or what functions the type has (including whether it has a default constructor).

A class definition has a body and lets you know the class’s size and know the names and types of its members:

class widget { // "{" means definition

widget();

// ...

};

widget* p; // ok: allocs sizeof(ptr) space typed as widget*

widget w; // ok: allocs sizeof(widget) space typed as widget

// and calls default constructor

2. In the following header file, what #include directives could be immediately removed without ill effect?

Of the first two standard headers mentioned in x.h, one can be immediately removed because it’s not needed at all, and the second can be replaced with a smaller header:

1. Remove iostream.

#include <iostream>

Many programmers #include <iostream> purely out of habit as soon as they see anything resembling a stream nearby. Class X does make use of streams, that’s true; but it doesn’t mention anything specifically from iostream, which mainly declares the standard stream objects like cout. At the most, X needs ostream alone for its basic_ostream type, and even that can be whittled down as we will see.

Guideline: Never #include unnecessary header files.

2. Replace ostream with iosfwd.

#include <ostream>

Parameter and return types only need to be forward-declared, so instead of the full definition of ostream we really only need its forward declaration.

However, you can’t write the forward declaration yourself using something like class ostream;. First, ostream lives in namespace std in which you can’t redeclare existing standard types and objects. Second, ostream is an alias for basic_ostream<char> which you couldn’t reliably forward-declare even if you were allowed to because library implementations are allowed to do things like add their own extra template parameters beyond those required by the standard that of course your code wouldn’t know about—which is one of the primary reasons for the rule that programmers aren’t allowed to write their own declarations for things in namespace std.

All is not lost, though: The standard library helpfully provides the header iosfwd, which contains forward declarations for all of the stream templates and their standard aliases, including basic_ostream and ostream. So all we need to do is replace #include <ostream> with #include <iosfwd>.

Guideline: Prefer to #include <iosfwd> when a forward declaration of a stream will suffice.

Incidentally, once you see iosfwd, one might think that the same trick would work for other standard library templates like string and list. There are, however, no comparable “stringfwd” or “listfwd” standard headers. The iosfwd header was created to give streams special treatment for backwards compatibility, to avoid breaking code written in years past for the “old” non-templated version of the iostreams subsystem. It is hoped that a real solution will come in a future version of C++ that supports modules, but that’s a topic for a later time.

There, that was easy. We can now move on to…

… what? “Not so fast!” I hear some of you say. “This header does a lot more with ostream than just mention it as a parameter or return type. The inlined operator<< actually uses an ostream object! So it must need ostream‘s definition, right?”

That’s a reasonable question. Happily, the answer is: No, it doesn’t. Consider again the function in question:

std::ostream& operator<<( std::ostream& os, const X& x ) {

return x.print(os);

}

This function mentions an ostream& as both a parameter and a return type, which most people know doesn’t require a definition. And it passes its ostream& parameter in turn as a parameter to another function, which many people don’t know doesn’t require a definition either—it’s the same as if it were a pointer, ostream*, discussed above. As long as that’s all we’re doing with the ostream&, there’s no need for a full ostream definition—we’re not really using an ostream itself at all, such as by calling functions on it, we’re only using a reference to type for which we only need to know the name. Of course, we would need the full definition if we tried to call any member functions, for example, but we’re not doing anything like that here.

So, as I was saying, we can now move on to get rid of one of the other headers, but only one just yet:

3. Replace e.h with a forward declaration.

#include "e.h" // class E

Class E is just being mentioned as a parameter and as a return type in function E h(E), so no definition is required and x.h shouldn’t be pulling in e.h in the first place because the caller couldn’t even be calling this function if he didn’t have the definition of E already, so there’s no point in including it again. (Note this would not be true if E were only a return type, such as if the signature were E h();, because in that case it’s good style to include E’s definition for the caller’s convenience so he can easily write code like auto val = x.h();.) All we need to do is replace #include “e.h” with class E;.

Guideline: Never #include a header when a forward declaration will suffice.

That’s it.

You may be wondering why we can’t get rid of the other headers yet. It’s because to define class X means you need to know its size in order to know how much space to allocate for an X object, and to know X’s size you need to know at least the size of every base class and data member. So we need the definitions of A and B because they are base classes, and we need the header definitions of list, C, and D because they are used to define the data members. How we can begin to address some of these is the subject of Part 2…

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the following for their feedback to improve this article: Gennaro, Sebastien Redl, Emmanuel Thivierge.

I see the recording went live this morning. Thanks again to all the speakers and in-room and worldwide attendees for coming and watching!

I see the recording went live this morning. Thanks again to all the speakers and in-room and worldwide attendees for coming and watching!

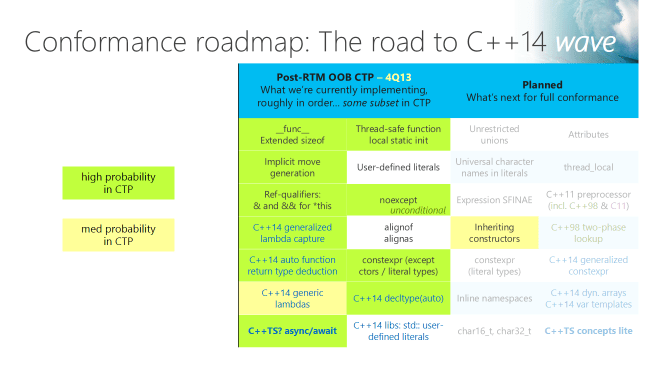

At Build in June, we announced that VC++ 2013 RTM “later this year” would include the ISO conformance features in the June preview (explicit conversion operators, raw string literals, function template default arguments, delegating constructors, uniform initialization and initializer_lists, and variadic templates) plus also several more to be added between the Preview and the RTM: non-static data member initializers, =default, =delete, “using” aliases, and library support for same plus four C99 features.

At Build in June, we announced that VC++ 2013 RTM “later this year” would include the ISO conformance features in the June preview (explicit conversion operators, raw string literals, function template default arguments, delegating constructors, uniform initialization and initializer_lists, and variadic templates) plus also several more to be added between the Preview and the RTM: non-static data member initializers, =default, =delete, “using” aliases, and library support for same plus four C99 features.

Don’t forget that the year’s great C++-fest

Don’t forget that the year’s great C++-fest