This GotW was written to answer a set of related frequently asked questions. So here’s a mini-FAQ on “thread safety and synchronization in a nutshell,” and the points we’ll cover apply to thread safety and synchronization in pretty much any mainstream language.

Problem

JG Questions

1. What is a race condition, and how serious is it?

2. What is a correctly synchronized program? How do you achieve it? Be specific.

Guru Questions

3. Consider the following code, where some_obj is a shared variable visible to multiple threads.

// thread 1 (performs no additional synchronization)

code_that_reads_from( some_obj ); // passes some_obj by const &

// thread 2 (performs no additional synchronization)

code_that_modifies( some_obj ); // passes some_obj by non-const &

If threads 1 and 2 can run concurrently, is this code correctly synchronized if the type of some_obj is:

(a) int?

(b) string?

(c) vector<map<int,string>>?

(d) shared_ptr<widget>?

(e) mutex?

(f) condition_variable?

(g) atomic<unsigned>?

Hint: This is actually a two-part question, not a seven-part question. There are only two unique answers, each of which covers a subset of the cases.

4. External synchronization means that the code that uses/owns a given shared object is responsible for performing synchronization on that object. Answer the following questions related to external synchronization:

(a) What is the normal external synchronization responsibility of code that owns and uses a given shared variable?

(b) What is the “basic thread safety guarantee” that all types must obey to enable calling code to perform normal external synchronization?

(c) What partial internal synchronization can still be required within the shared variable’s implementation?

5. Full internal synchronization (a.k.a. “synchronized types” or “thread-safe types”) means that a shared object performs all necessary synchronization internally within that object, so that calling code does not need to perform any external synchronization. What types should be fully internally synchronized, and why?

Solution

Preface

The discussion in this GotW applies not only to C++ but also to any mainstream language, except mainly that certain races have defined behavior in C# and Java. But the definition of what variables need to be synchronized, the tools we use to synchronize them, and the distinction between external and internal synchronization and when you use each one, are the same in all mainstream languages. If you’re a C# or Java programmer, everything here applies equally to you, with some minor renaming such as to rename C++ atomic to C#/Java volatile, although some concepts are harder to express in C#/Java (such as identifying the read-only methods on an otherwise mutable shared object; there are readonly fields and “read-only” properties that have get but not set, but they express a subset of what you can express using C++ const on member functions).

Note: C++ volatile variables (which have no analog in languages like C# and Java) are always beyond the scope of this and any other article about the memory model and synchronization. That’s because C++ volatile variables aren’t about threads or communication at all and don’t interact with those things. Rather, a C++ volatile variable should be viewed as portal into a different universe beyond the language — a memory location that by definition does not obey the language’s memory model because that memory location is accessed by hardware (e.g., written to by a daughter card), have more than one address, or is otherwise “strange” and beyond the language. So C++ volatile variables are universally an exception to every guideline about synchronization because are always inherently “racy” and unsynchronizable using the normal tools (mutexes, atomics, etc.) and more generally exist outside all normal of the language and compiler including that they generally cannot be optimized by the compiler (because the compiler isn’t allowed to know their semantics; a volatile int vi; may not behave anything like a normal int, and you can’t even assume that code like vi = 5; int read_back = vi; is guaranteed to result in read_back == 5, or that code like int i = vi; int j = vi; that reads vi twice will result in i == j which will not be true if vi is a hardware counter for example). For more discussion, see my article “volatile vs. volatile.”

1. What is a race condition, and how serious is it?

A race condition occurs when two threads access the same shared variable concurrently, and at least one is a non-const operation (writer). Concurrent const operations are valid, and do not race with each other.

Consecutive nonzero-length bitfields count as a single variable for the purpose of defining what a race condition is.

Terminology note: Some people use “race” in a different sense, where in a program with no actual race conditions (as defined above) still operations on different threads could interleave in different orders in different executions of a correctly-synchronized program depending on how fast threads happen to execute relative to each other. That’s not a race condition in the sense we mean here—a better term for that might be “timing-dependent code.”

If a race condition occurs, your program has undefined behavior. C++ does not recognize any so-called “benign races”—and in languages that have recognized some races as “benign” the community has gradually learned over time that many of them actually, well, aren’t.

Guideline: Reads (const operations) on a shared object are safe to run concurrently with each other without synchronization.

2. What is a correctly synchronized program? How do you achieve it? Be specific.

A correctly synchronized program is one that contains no race conditions. You achieve it by making sure that, for every shared variable, every thread that performs a write (non-const operation) on that variable is synchronized so that no other reads or writes of that variable on other threads can run concurrently with that write.

The shared variable usually protected by:

- (commonly) using a mutex or equivalent;

- (very rarely) by making it atomic if that’s appropriate, such as in low-lock code; or

- (very rarely) for certain types by performing the synchronization internally, as we will see below.

3. Consider the following code… If threads 1 and 2 can run concurrently, is this code correctly synchronized if the type of some_obj is: (a) int? (b) string? (c) vector<map<int,string>>? (d) shared_ptr<widget>?

No. The code has one thread reading (via const operations) from some_obj, and a second thread writing to the same variable. If those threads can execute at the same time, that’s a race and a direct non-stop ticket to undefined behavior land.

The answer is to synchronize access to the variable, for example using a mutex:

// thread 1

{

lock_guard hold(mut_some_obj); // acquire lock

code_that_reads_from( some_obj ); // passes some_obj by const &

}

// thread 2

{

lock_guard hold(mut_some_obj); // acquire lock

code_that_modifies( some_obj ); // passes some_obj by non-const &

}

Virtually all types, including shared_ptr and vector and other types, are just as thread-safe as int; they’re not special for concurrency purposes. It doesn’t matter whether some_obj is an int, a string, a container, or a smart pointer… concurrent reads (const operations) are safe without synchronization, but the shared object is writeable, then the code that owns the object has to synchronize access to it.

But when I said this is true for “virtually all types,” I meant all types except for types that are not fully internally synchronized, which brings us to the types that, by design, are special for concurrency purposes…

… If threads 1 and 2 can run concurrently, is this code correctly synchronized if the type of g+shared is: (e) mutex? (f) condition_variable? (g) atomic<unsigned>?

Yes. For these types, the code is okay, because these types already perform full internal synchronization and so they are safe to access without external synchronization.

In fact, these types had better be safe to use without external synchronization, because they’re synchronization primitives you need to use as tools to synchronize other variables! And its turns out that that’s no accident…

Guideline: A type should only be fully internally synchronized if and only if its purpose is to provide inter-thread communication (e.g., a message queue) or synchronization (e.g., a mutex).

4. External synchronization means that the code that uses/owns a given shared object is responsible for performing synchronization on that object. Answer the following questions related to external synchronization:

(a) What is the normal external synchronization responsibility of code that owns and uses a given shared variable?

The normal synchronization duty of care is simply this: The code that knows about and owns a writeable shared variable has to synchronize access to it. It will typically do that using a mutex or similar (~99.9% of the time), or by making it atomic if that’s possible and appropriate (~0.1% of the time).

Guideline: The code that knows about and owns a writeable shared variable is responsible for synchronizing access to it.

(b) What is the “basic thread safety guarantee” that all types must obey to enable calling code to perform normal external synchronization?

To make it possible for the code that uses a shared variable to do the above, two basic things must be true.

First, concurrent operations on different objects must be safe. For example, let’s say we have two X objects x1 and x2, each of which is only used by one thread. Then consider this situation:

// Case A: Using distinct objects

// thread 1 (performs no additional synchronization)

x1.something(); // do something with x1

// thread 2 (performs no additional synchronization)

x2 = something_else; // do something else with x2

This must always be considered correctly synchronized. Remember, we stated that x1 and x2 are distinct objects, and cannot be aliases for the same object or similar hijinks.

Second, concurrent const operations that are just reading from the same variable x must be safe:

// Case B: const access to the same object

// thread 1 (performs no additional synchronization)

x.something_const(); // read from x (const operation)

// thread 2 (performs no additional synchronization)

x.something_else_const(); // read from x (const operation)

This code too must be considered correctly synchronized, and had better work without external synchronization. It’s not a race, because the two threads are both performing const accesses and reading from the shared object.

This brings us to the case where there might be a combination of internal and external synchronization required…

(c) What partial internal synchronization can still be required within the shared variable’s implementation?

In some classes, objects that from the outside appear to be distinct but still may share state under the covers, without the calling code being able to tell that two apparently distinct objects are connected under the covers. Note that this not an exception to the previous guideline—it’s the same guideline!

Guideline: It is always true that the code that knows about and owns a writeable shared variable is responsible for synchronizing access to it. If the writeable shared state is hidden inside the implementation of some class, then it’s simply that class’ internals that are the ‘owning code’ that has to synchronize access to (just) the shared state that only it knows about.

A classic case of “under-the-covers shared state” is reference counting, and the two poster-child examples are std::shared_ptr and copy-on-write. Let’s use shared_ptr as our main example.

A reference-counted smart pointer like shared_ptr keeps a reference count under the covers. Let’s say we have two distinct shared_ptr objects sp1 and sp2, each of which is used by only one thread. Then consider this situation:

// Case A: Using distinct objects

// thread 1 (performs no additional synchronization)

auto x = sp1; // read from sp1 (writes the count!)

// thread 2 (performs no additional synchronization)

sp2 = something_else; // write to sp2 (writes the count!)

This code must be considered correctly synchronized, and had better work as shown without any external synchronization. Okay, fine …

… but what if sp1 and sp2 are pointing to the same object and so share a reference count? If so, that reference count is a writeable shared object, and so it must be synchronized to avoid a race—but it is in general impossible for the calling code to do the right synchronization, because it is not even aware of the sharing! The code we just saw above doesn’t see the count, doesn’t know the count variable’s name, and doesn’t in general know which pointers share counts.

Similarly, consider two threads just reading from the same variable sp:

// Case B: const access to the same object

// thread 1 (performs no additional synchronization)

auto sp3 = sp; // read from sp (writes the count!)

// thread 2 (performs no additional synchronization)

auto sp4 = sp; // read from sp (writes the count!)

This code too must be considered correctly synchronized, and had better work without external synchronization. It’s not a race, because the two threads are both performing const accesses and reading from the shared object. But under the covers, reading from sp to copy it increments the reference count, and so again that reference count is a writeable shared object, and so it must be synchronized to avoid a race—and again it is in general impossible for the calling code to do the right synchronization, because it is not even aware of the sharing.

So to deal with these cases, the code that knows about the shared reference count, namely the shared_ptr implementation, has to synchronize access to the reference count. For reference counting, this is typically done by making the reference count a mutable atomic variable. (See also GotW #6a and #6b.)

For completeness, yes, of course external synchronization is still required as usual if the calling code shared a given visible shared_ptr object and makes that same shared_ptr object writable across threads:

// Case C: External synchronization still required as usual

// for non-const access to same visible shared object

// thread 1

{

lock_guard hold(mut_sp); // acquire lock

auto sp3 = sp; // read from sp

}

// thread 2

{

lock_guard hold(mut_sp); // acquire lock

sp = something_else; // modify sp

}

So it’s not like shared_ptr is a fully internally synchronized type; if the caller is sharing an object of that type, the caller must synchronize access to it like it would do for other types, as noted in Question 3(d).

So what’s the purpose of the internal synchronization? It’s only to do necessary synchronization on the parts that the internals know are shared and that the internals own, but that the caller can’t synchronize because he doesn’t know about the sharing and shouldn’t need to because the caller doesn’t own them, the internals do. So in the internal implementation of the type we do just enough internal synchronization to get back to the level where the caller can assume his usual duty of care and in the usual ways correctly synchronize any objects that might actually be shared.

The same applies to other uses of reference counting, such as copy-on-write strategies. It also applies generally to any other internal sharing going on under the covers between objects that appear distinct and independent to the calling code.

Guideline: If you design a class where two objects may invisibly share state under the covers, it is your class’ responsibility to internally synchronize access to that mutable shared state (only) that it owns and that only it can see, because the calling code can’t. If you opt for under-the-covers-sharing strategies like copy-on-write, be aware of the duty you’re taking on for yourself and code with care.

For why such internal shared state should be mutable, see GotW #6a and #6b.

5. … What types should be fully internally synchronized, and why?

There is exactly one category of types which should be fully internally synchronized, so that any object of that type is always safe to use concurrently without external synchronization: Inter-thread synchronization and communication primitives themselves. This includes standard types like mutexes and atomics, but also inter-thread communication and synchronization types you might write yourself such as a message queue (communicating messages from one thread to another), Producer/Consumer active objects (again passing data from one concurrent entity to another), or a thread-safe counter (communicating counter increments and decrements among multiple threads).

If you’re wondering if there might be other kinds of types that should be internally synchronized, consider: The only type for which it would make sense to always internally synchronize every operation is a type where you know every object is going to be both (a) writeable and (b) shared across threads… and that means that the type is by definition designed to be used for inter-thread communication and/or synchronization.

Acknowledgments

Thanks in particular to the following for their feedback to improve this article: Daniel Hardman, Casey, Alb, Marcel Wid, ixache.

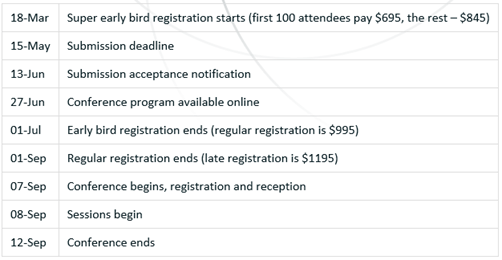

More news about the first annual CppCon that was announced last week:

More news about the first annual CppCon that was announced last week:

PS on the

PS on the  It has occurred to me that I never announced this event here…

It has occurred to me that I never announced this event here…