2025 was another great year for C++. It shows in the numbers

Before we dive into the data below, let’s put the most important question up front: Why have C++ and Rust been the fastest-growing major programming languages from 2022 to 2025?

Primarily, it’s because throughout the history of computing “software taketh away faster than hardware giveth.” There is enduring demand for efficient languages because our demand for solving ever-larger computing problems consistently outstrips our ability to build greater computing capacity, with no end in sight. [6] Every few years, people wonder whether our hardware is just too fast to be useful, until the future’s next big software demand breaks across the industry in a huge wake-up moment of the kind that iOS delivered in 2007 and ChatGPT delivered in November 2022. AI is only the latest source of demand to squeeze the most performance out of available hardware.

The world’s two biggest computing constraints in 2025

Quick quiz: What are the two biggest constraints on computing growth in 2025? What’s in shortest supply?

Take a moment to answer that yourself before reading on…

— — —

If you answered exactly “power and chips,” you’re right — and in the right order.

Chips are only our #2 bottleneck. It’s well known that the hyperscalars are competing hard to get access to chips. That’s why NVIDIA is now the world’s most valuable company, and TSMC is such a behemoth that it’s our entire world’s greatest single point of failure.

But many people don’t realize: Power is the #1 constraint in 2025. Did you notice that all the recent OpenAI deals were expressed in terms of gigawatts? Let’s consider what three C-level executives said on their most recent earnings calls. [1]

Amy Hood, Microsoft CFO (MSFT earnings call, October 29, 2025):

[Microsoft Azure’s constraint is] not actually being short GPUs and CPUs per se, we were short the space or the power, is the language we use, to put them in.

Andy Jassy, Amazon CEO (AMZN earnings call, October 30, 2025):

[AWS added] more than 3.8 gigawatts of power in the past 12 months, more than any other cloud provider. To put that into perspective, we’re now double the power capacity that AWS was in 2022, and we’re on track to double again by 2027.

Jensen Huang, NVIDIA CEO (NVDA earnings call, November 19, 2025):

The most important thing is, in the end, you still only have 1 gigawatt of power. One gigawatt data centers, 1 gigawatt power. … That 1 gigawatt translates directly. Your performance per watt translates directly, absolutely directly, to your revenues.

That’s why the future is enduringly bright for languages that are efficient in “performance per watt” and “performance per transistor.” The size of computing problems we want to solve has routinely outstripped our computing supply for the past 80 years; I know of no reason why that would change in the next 80 years. [2]

The list of major portable languages that target those key durable metrics is very short: C, C++, and Rust. [3] And so it’s no surprise to see that in 2025 all three continued experiencing healthy growth, but especially C++ and Rust.

Let’s take a look.

The data in 2025: Programming keeps growing by leaps and bounds, and C++ and Rust are growing fastest

Programming is a hot market, and programmers are in long-term high-growth demand. (AI is not changing this, and will not change it; see Appendix.)

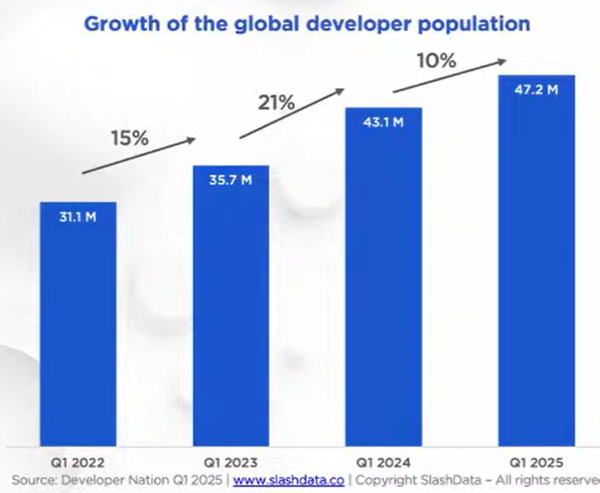

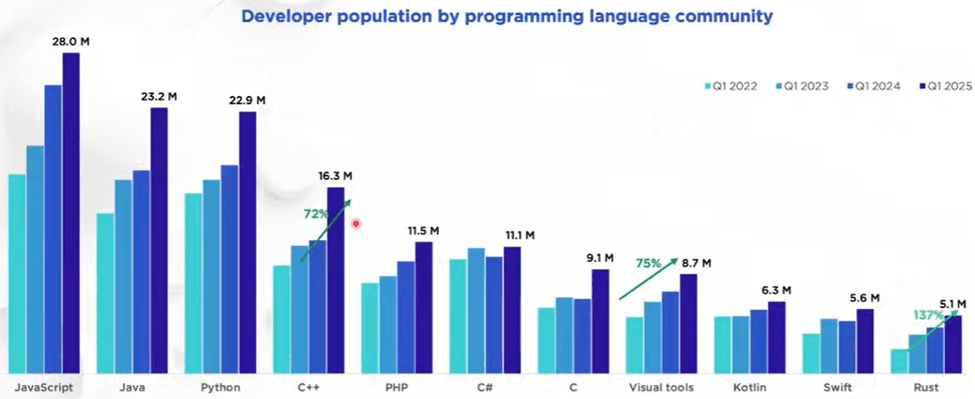

“Global developer population trends 2025” (SlashData, 2025) reports that in the past three years the global developer population grew about 50%, from just over 31 million to just over 47 million. (Other sources are consistent with that: IDC forecasts that this growth will continue, to over 57 million developers by 2028. JetBrains reports similar numbers of professional developers; their numbers are smaller because they exclude students and hobbyists.) And which two languages are growing the fastest (highest percentage growth from 2022 to 2025)? Rust, and C++.

To put C++’s growth in context:

- Compared to all languages: There are now more C++ developers than the #1 language had just four years ago.

- Compared to Rust: Each of C++, Python, and Java just added about as many developers in one year as there are Rust total developers in the world.

C++ is a living language whose core job to be done is to make the most of hardware, and it is continually evolving to stay relevant to the changing hardware landscape. The new C++26 standard contains additional support for hardware parallelism on the latest CPUs and GPUs, notably adding more support for SIMD types for intra-CPU vector parallelism, and the std::execution Sender/Receiver model for general multi-CPU and GPU concurrency and parallelism.

But wait — how could this growth be happening? Isn’t C++ “too unsafe to use,” according to a spate of popular press releases and tweets by a small number of loud voices over the past few years?

Let’s tackle that next…

Safety (type/memory safety, functional safety) and security

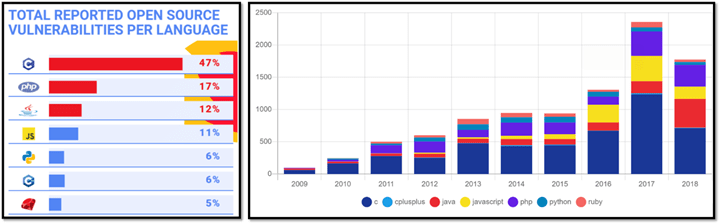

C++’s rate of security vulnerabilities has been far overblown in the press primarily because some reports are counting only programming language vulnerabilities when those are a smaller minority every year, and because statistics conflate C and C++. Let’s consider those two things separately.

First, the industry’s security problem is mostly not about programming language insecurity.

Year after year, and again in 2025, in the MITRE “CWE Top 25 Most Dangerous Software Weaknesses” (mitre.org, 2025) only three of the top 10 “most dangerous software weaknesses” are related to language safety properties. Of those three, two (out-of-bounds write and out-of-bounds read) are directly and dramatically improved in C++26’s hardened C++ standard library which does bounds-checking for the most widely used bounded operations (see below). And that list is only about software weaknesses, when more and more exploits bypass software entirely.

Why are vulnerabilities increasingly not about language issues, or even about software at all? Because we have been hardening our software; this is why the cost of zero-day exploits has kept rising, from thousands to millions of dollars. So attackers stop pursuing that as much, and switch to target the next slowest animal in the herd. For example, “CrowdStrike 2025 Global Threat Report” (CrowdStrike, 2025) reports that “79% of [cybersecurity intrusion] detections were malware-free,” not involving programming language exploits. Instead, there was huge growth not only in non-language exploits, but even in non-software exploits, including a “442% growth in vishing [voice phishing via phone calls and voice messages] operations between the first and second half of 2024.”

Why go to the trouble of writing an exploit for a use-after-free bug to infect someone’s computer with malware which is getting more expensive every year, when it’s easier to do some cross-site scripting that doesn’t depend on a programming language insecurity, and it’s easier still to ignore the software entirely and just convince the user to tell you their password on the phone?

Second, for the subset that is about programming language insecurity, the problem child is C, not C++.

A serious problem is that vulnerability statistics almost always conflate C and C++; it’s very hard to find good public sources that distinguish them. The only reputable public study I know of that distinguished between C and C++ is Mend.io’s as reported in “What are the most secure programming languages?” (Mend.io, 2019). Although the data is from 2019, as you can see the results are consistent across years.

Can’t see the C++ bar? Pinch to zoom. 😉

Although C++’s memory safety has always been much closer to that of other modern popular languages than to that of C, we do have room for improvement and we’re doing even better in the newest C++ standard about to be released, C++26. It delivers two major security improvements, where you can just recompile your code as C++26 and it’s significantly more secure:

- C++26 eliminates undefined behavior from uninitialized local variables. [4] How needed is this? Well, it directly addresses a Reddit r/cpp complaint posted just today while I was finishing this post: “The production bug that made me care about undefined behavior” (Reddit, December 30, 2025).

- C++26 adds bounds safety to the C++ standard library in a “hardened” mode that bounds-checks the most widely used bounded operations. “Practical Security in Production” (ACM Queue, November 2025) reports that it has already been used at scale across Apple platforms (including WebKit) and nearly all Google services and Chrome (100s of millions of lines of code) with tiny space and time overhead (fraction of one percent each), and “is projected to prevent 1,000 to 2,000 new bugs annually” at Google alone.

Additionally, C++26 adds functional safety via contracts: preconditions, postconditions, and contract assertions in the language, that programmers can use to check that their programs behave as intended well beyond just memory safety.

Beyond C++26, in the next couple of years I expect to see proposals to:

- harden more of the standard library

- remove more undefined behavior by turning it into erroneous behavior, turning it into language-enforced contracts, or forbidding it via subsets that ban unsafe features by default unless we explicitly opt in (aka profiles)

I know of people who’ve been asking for C++ evolution to slow down a little to let compilers and users catch up, something like we did for C++03. But we like all this extra security, too. So, just spitballing here, but hypothetically:

What if we focused C++29, the next release cycle of C++, to only issue-list-level items (bug fixes and polish, not new features) and the above “hardening” list (add more library hardening, remove more language undefined behavior)?

I’m intrigued by this idea, not because security is C++’s #1 burning issue — it isn’t, C++ usage is continuing to grow by leaps and bounds — but because it could address both the “let’s pause to stabilize” and “let’s harden up even more” motivations. Focus is about saying no.

Conclusion

Programming is growing fast. C++ is growing very fast, with a healthy long-term future because it’s deeply aligned with the overarching 80-year trend that computing demand always outstrips supply. C++ is a living language that continually adapts to its environment to fulfill its core mission, tracking what developers need to make the most of hardware.

And it shows in the numbers.

Here’s to C++’s great 2025, and its rosy outlook in 2026! I hope you have an enjoyable rest of the holiday period, and see you again in 2026.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Saeed Amrollahi Boyouki, Mark Hoemmen and Bjarne Stroustrup for motivating me to write this post and/or providing feedback.

Appendix: AI

Finally, let’s talk about the topic no article can avoid: AI.

C++ is foundational to current AI. If you’re running AI, you’re running CUDA (or TensorFlow or similar) — directly or indirectly — and if you’re running CUDA (or TensorFlow or similar), you’re probably running C++. CUDA is primarily available as a C++ extension. There’s always room for DSLs at the leading edge, but for general-purpose AI most high-performance deployment and inference is implemented in C++, even if people are writing higher-level code in other languages (e.g., Python).

But more broadly than just C++: What about AI generally? Will it take all our jobs? (Spoiler: No.)

AI is a wonderful and transformational tool that greatly reduces rote work, including problems that have already been solved, where the LLM is trained on the known solutions. But AI cannot understand, and therefore can’t solve, new problems — which is most of the current and long-term growth in our industry.

What does that imply? Two main things, in my opinion…

First, I think that people who think AI isn’t a major game-changer are fooling themselves.

To me, AI is on par with the wheel (back in the mists of time), the calculator (back in the 1970s), and the Internet (back in the 1990s). [5] Each of those has been a game-changing tool to accelerate (not replace) human work, and each led to more (not less) human production and productivity.

I strongly recommend checking out Adam Unikowsky’s “Automating Oral Argument” (Substack, July 7, 2025). Unikowsky took his own actual oral arguments before the United States Supreme Court and showed how well 2025-era Claude can do as a Supreme Court-level lawyer, and with what strengths and weaknesses. Search for “Here is the AI oral argument” and click on the audio player, which is a recording of an actual Supreme Court session and replaces only Unikowsky’s responses with his AI-generated voice saying the AI-generated text argument directly responding to each of the justices’ actual questions; the other voices are the real Supreme Court justices. (Spoiler: “Objectively, this is an outstanding oral argument.”)

Second, I think that people who think AI is going to put a large fraction of programmers out of work are fooling themselves.

We’ve just seen that, today, three years after ChatGPT took the world by storm, the number of human programmers is growing as fast as ever. Even the companies that are the biggest boosters of the “AI will replace programmers” meme are actually aggressively growing, not reducing, their human programmer workforces.

Consider what three more C-level executives are saying.

Sam Schillace, Microsoft Deputy CTO (Substack, December 19, 2025) is pretty AI-ebullient, but I do agree with this part he says well, and which resonates directly with Unikowsky’s experience above:

If your job is fundamentally “follow complex instructions and push buttons,” AI will come for it eventually.

But that’s not most programmers. Matt Garman, Amazon Web Services CEO (interview with Matthew Berman, X, August 2025) says bluntly:

People were telling me [that] with AI we can replace all of our junior people in our company. I was like that’s … one of the dumbest things I’ve ever heard. … I think AI has the potential to transform every single industry, every single company, and every single job. But it doesn’t mean they go away. It has transformed them, not replaced them.

Mike Cannon-Brookes, Atlassian CEO (Stratechery interview, December 2025) says it well:

I think [AI]’s a huge force multiplier personally for human creativity, problem solving … If software costs half as much to write, I can either do it with half as many people, but [due to] core competitive forces … I will [actually] need the same number of people, I would just need to do a better job of making higher quality technology. … People shouldn’t be afraid of AI taking their job … they should be afraid of someone who’s really good at AI [and therefore more efficient] taking their job.

So if we extend the question of “what are our top constraints on software?” to include not only hardware and power, the #3 long-term constraint is clear: We are chronically short of skilled human programmers. Humans are not being replaced en masse, not most of us; we are being made more productive, and we’re needed more than ever. As I wrote above: “Programming is a hot market, and programmers are in long-term high-growth demand.”

Endnotes

[1] It’s actually great news that Big Tech is spending heavily on power, because the gigawatt capacity we build today is a long-term asset that will keep working for 15 to 20+ years, whether the companies that initially build that capacity survive or get absorbed. That’s important because it means all the power generation being built out today to satisfy demand in the current “AI bubble” will continue to be around when the next major demand for compute after AI comes along. See Ben Thompson’s great writing, such as “The Benefits of Bubbles” (Stratechery, November 2025).

[2] The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy contains two opposite ideas, both fun but improbable: (1) The problem of being “too compute-constrained”: Deep Thought, the size of a city, wouldn’t really be allowed to run for 7.5 million years; you’d build a million cities. (2) The problem of having “too much excess compute capacity”: By the time a Marvin with a “brain the size of a planet” was built, he wouldn’t really be bored; we’d already be trying to solve problems the size of the solar system.

[3] This is about “general-purpose” coding. Code at the leading specialized edges will always include use of custom DSLs.

[4] This means that compiling plain C code (that is in the C/C++ intersection) as C++26 also automatically makes it more correct and more secure. This isn’t new; compiling C code as C++ and having the C code be more correct has been true since the 1980s.

[5] If you’re my age, you remember when your teacher fretted that letting you use a calculator would harm your education. More of you remember similar angsting about letting students google the internet. Now we see the same fears with AI — as if we could stop it or any of those others even if we should. And we shouldn’t; each time, we re-learn the lesson that teaching students to use such tools should be part of their education because using tools makes us more productive.

[6] This is not the same as Wirth’s Law, that “software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware is becoming faster.” Wirth’s observation was that the overheads of operating systems and higher-level runtimes and other costly abstractions were becoming ever heavier over time, so that a program to solve the same problem was getting more and more inefficient and soaking up more hardware capacity than it used to; for example, printing “Hello world” really does take far more power and hardware when written in modern Java than it did in Commodore 64 BASIC. That doesn’t apply to C++ which is not getting slower over time; C++ continues to be at least as efficient as low-level C for most uses. No, the key point I’m making here is very different: that the problems the software is tackling are growing faster than hardware is becoming faster.