Obligatory comment: The C++20 Eagle has wings.

At noon today, July 20 2019, the ISO C++ committee completed its summer meeting in Cologne, Germany, hosted with thanks by Think-Cell, SIGS Datacom, SimuNova, Silexica, Meeting C++, Josuttis Eckstein, Xara, Volker Dörr, Mike Spertus, and the Standard C++ Foundation.

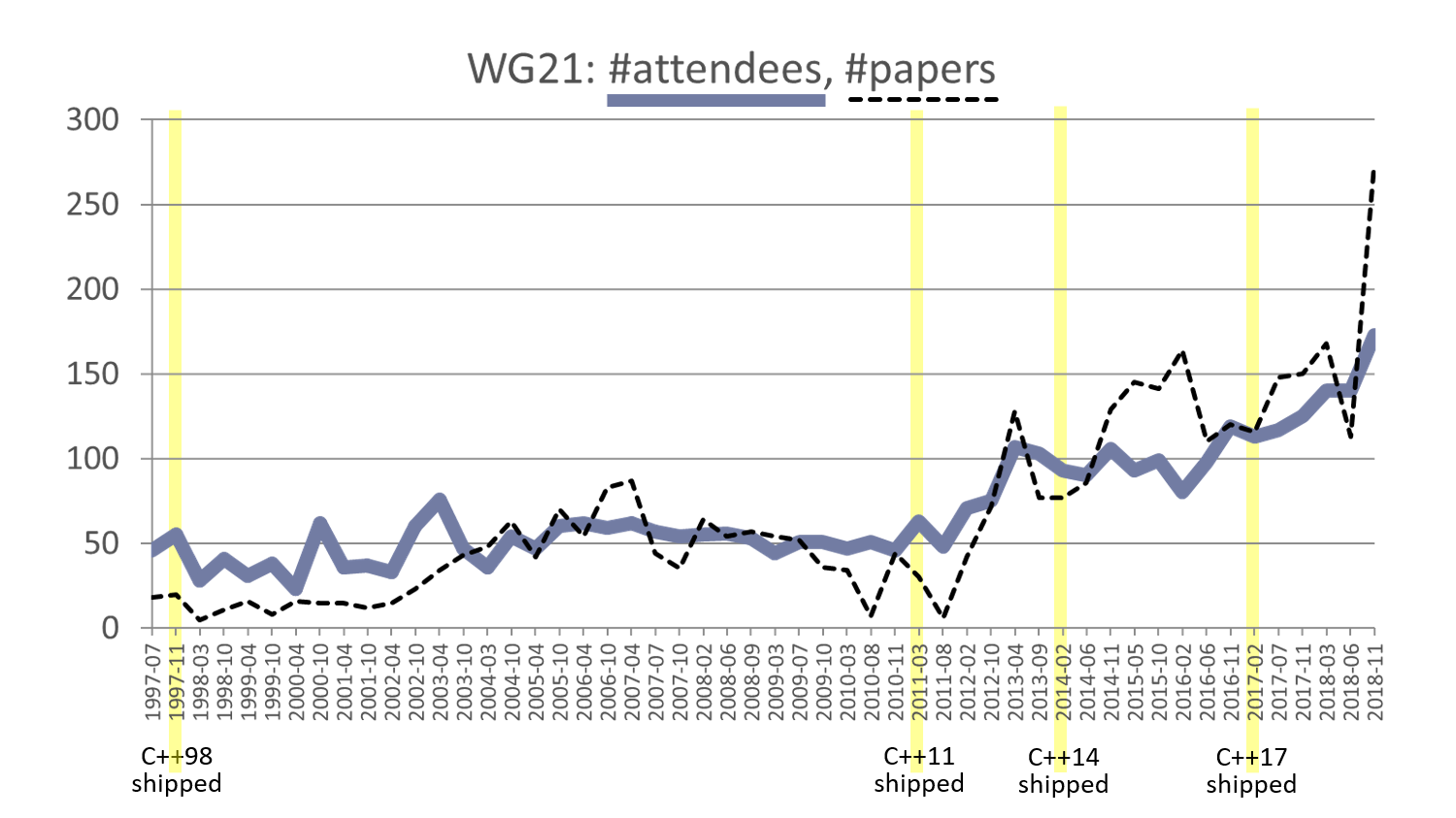

As usual, we met for six days Monday through Saturday, and it was our biggest meeting yet with some 220 attendees. Here’s a visual, going back to when I first joined the committee:

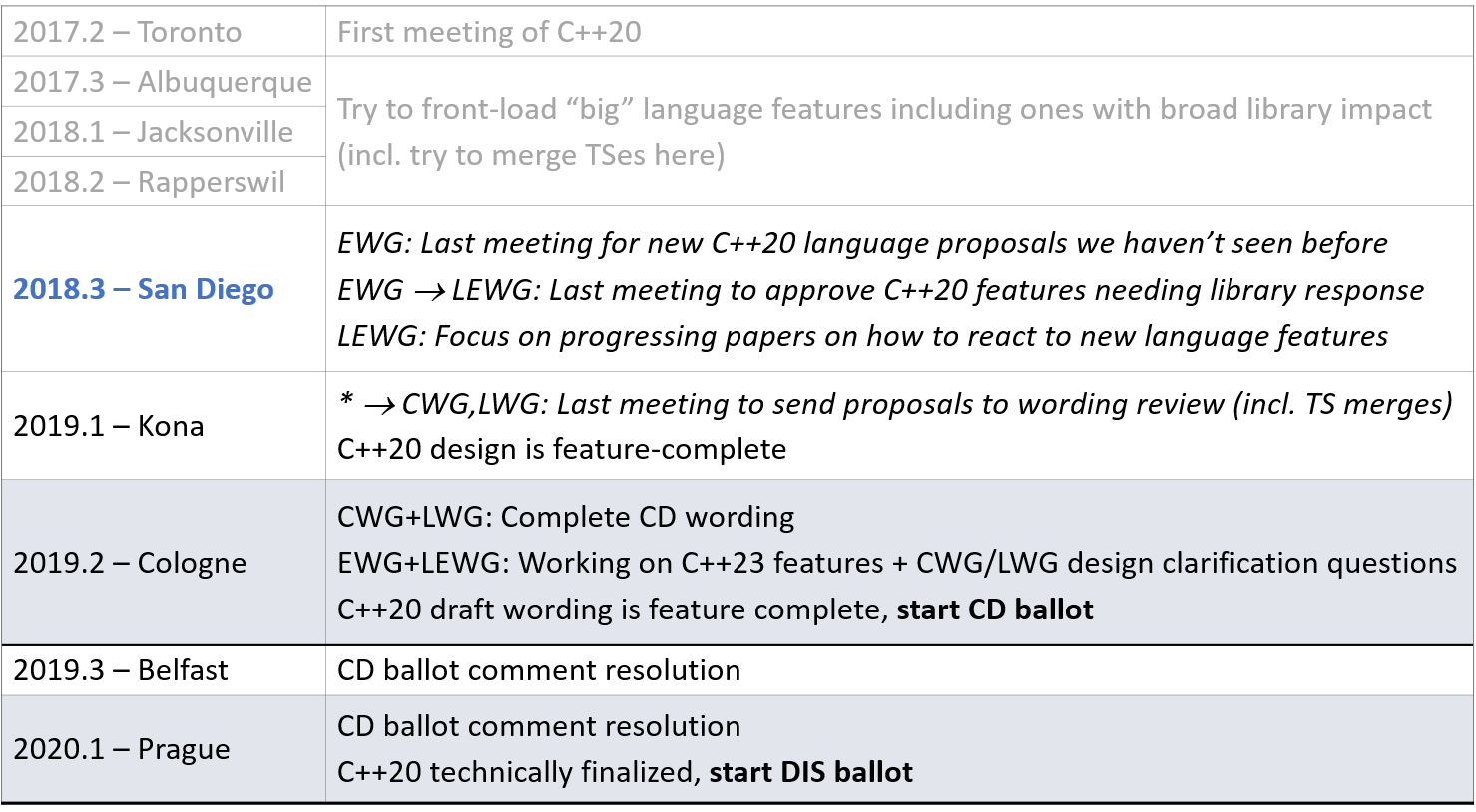

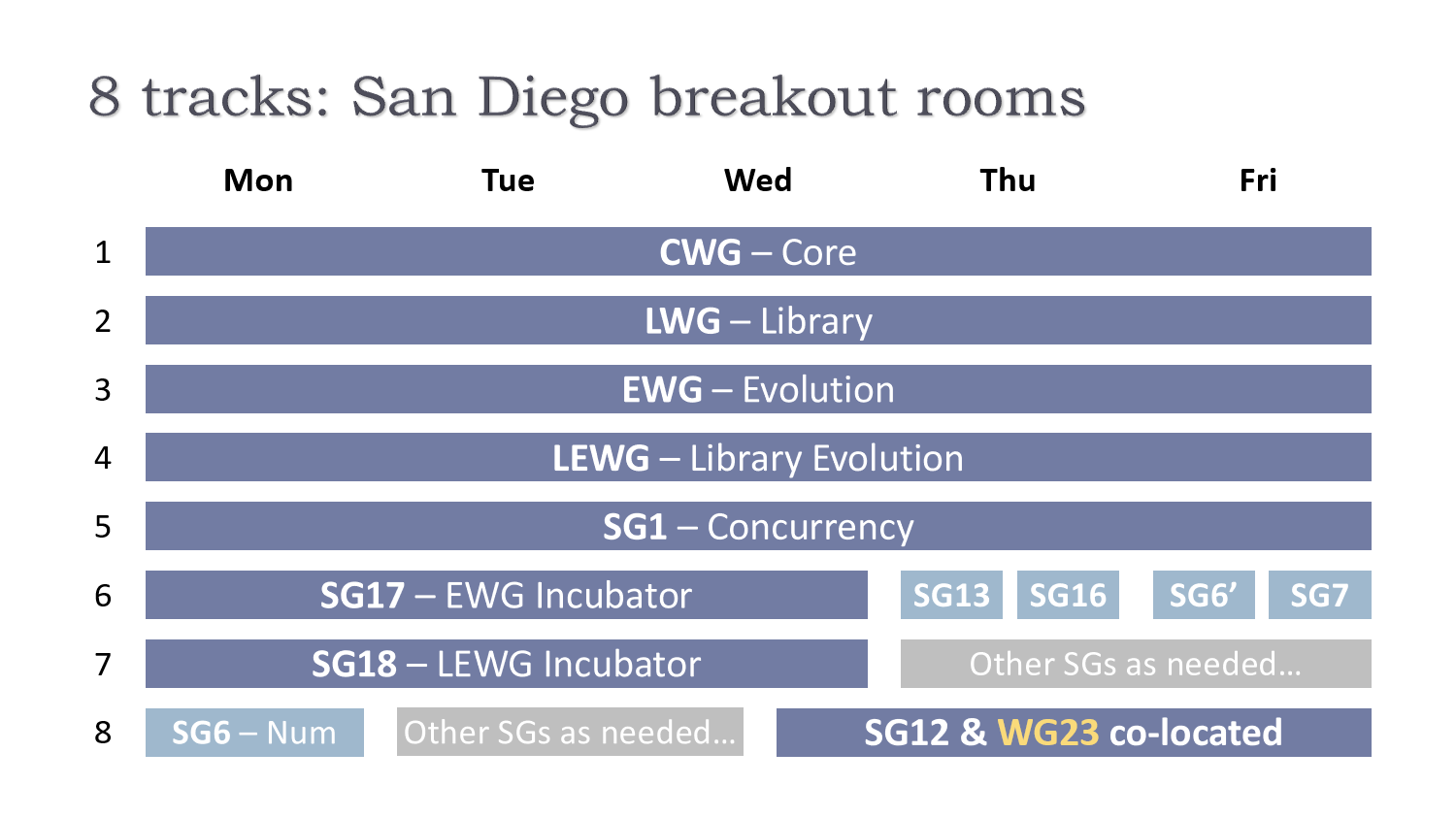

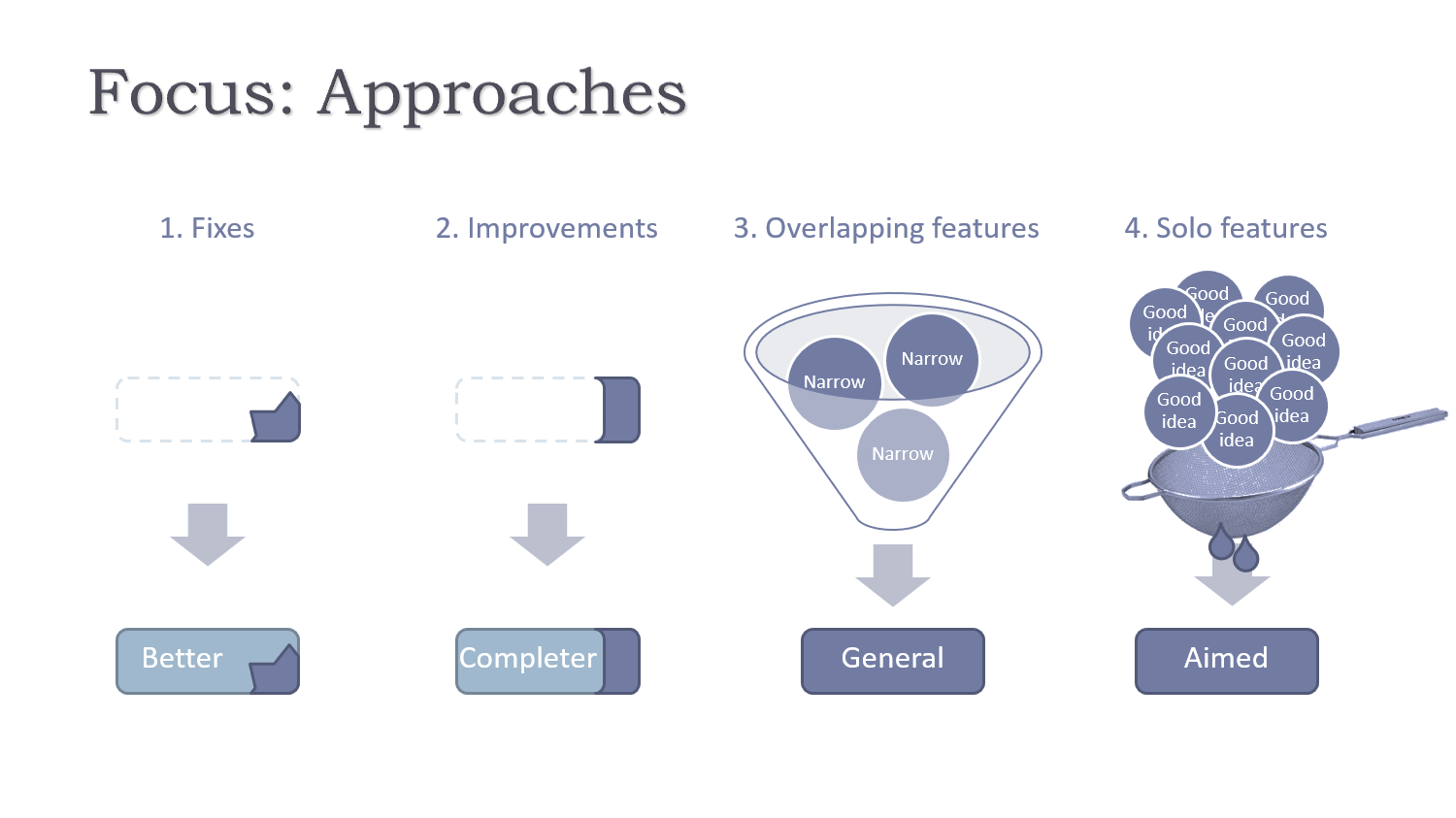

For more details about how we have adapted organizationally to handle our size increase, see my San Diego “pre-trip” report and my San Diego trip report.

Thank you to all of the hundreds of people who participate in ISO C++ in person and electronically. Below, I want to at least try to recognize by name many of the authors of the proposals we adopted, but nobody succeeds with a proposal on their own. C++ is a team effort – this wouldn’t be possible without all of your help. So, thank you, and apologies for not being able to acknowledge everyone by name.

Notes:

- See also the Reddit trip report, which was collaboratively edited by several dozen committee members. It has lots of excellent detail.

- Some of the links below are to papers that will not be published until the post-meeting mailing a few weeks from now, and so the links will start working at that time.

- You can find a brief summary of ISO procedures here.

The main news: C++20 is feature complete, CD ships

Today we achieved feature freeze for C++20.

Per our official C++20 schedule, we are now feature-complete for C++20 and will send out the C++20 draft for its international comment ballot (Committee Draft, or CD) to run over the summer. After that, we will address national body comments and other fit-and-finish work for the next two meetings (November in Belfast, and February in Prague) and plan to ship the final text of the C++20 start at the end of the February meeting.

Here are the main proposals that were added into C++20 at this meeting.

std::format for text formatting (Victor Zverovich) adds format strings support to the C++ standard library, including for type-safe and positional parameters. If you’re familiar with Boost.Format or POSIX format strings, or even just printf, you’ll know exactly what this is about: It gives us the best of printf (convenience) and the best of iostreams (type safety and extensibility of iostreams) – and it isn’t limited to iostreams, it lets you format any string. I’ve been waiting for this for a long time, so that I will never have to use header iomanip again.

Applying <=> (spaceship) comparisons throughout the standard library (Barry Revzin) uses the new <=> feature and applies it throughout namespace std to basically everything. It’s great to see a new language feature we added in C++20 already used widely in the standard library itself in the same release. And it’s not alone: C++20 also added concepts and also the concepts-based ranges library in the same release.

Stop token and joining thread (Nicolai Josuttis, Lewis Baker, Billy O’Neal, Herb Sutter, Anthony Williams) brings us two presents: First, a correctly RAII thread type whose destructor implicitly joins if you haven’t joined or detached already. And second, but even more importantly, a general composable cancellation mechanism into the standard library that all types can use, called stop_token.

And also, in the “moar constexpr!” and “constexpr all the things!” departments:

We added constexpr INVOKE (Tomasz Kamiński and Barry Revzin), constexpr std::vector (Louis Dionne), and constexpr std::string (Louis Dionne). If all this constexpr surprises you, and in particular if constexpr std::vector and std::string make you do a double-take: Remember that we already added constexpr new (think about that and grok what it means) and made much of the standard library constexpr and added consteval to the language… and all told this means that a whole lot of ordinary C++ code can run at compile time, now including even the standard dynamic vector and string containers. This is something that would have been difficult to imagine just a few years ago, but it shows ever more that we’re on a path where we can run plain C++ code at compile time instead of trying to express those computations as template metaprograms. As many people have said: “More metaprogramming, less template metaprogramming!” We didn’t have to invent a new ‘compile-time C++’ dialect; this is just C++, running at compile time. This trend is good.

There are dozens of additional proposals we adopted besides these, all of them good work, and I want to repeat our great thanks to all the proposal authors and also the even larger number of people who helped them with their proposals without whom this could not have happened. Thank you for your time and effort on behalf of millions of C++ developers worldwide who will benefit from your hard and careful work!

Contracts moved from draft C++20 to a new Study Group

At this meeting, it became clear that we were not quite done designing the contracts feature in time for C++20. Back when we adopted the feature one year ago we thought it was baked and ready for the standard, but since then we have discovered lingering design disagreements and concerns that we could not resolve sufficiently to get consensus (general agreement without sustained objections). All the main contracts proposers unanimously agreed that the right thing to do is to defer its release.

But contracts is an important feature, and work on contracts is not stopping, but actually increasing: The contracts proposers made good progress at this meeting toward starting to identify and iron out the differences, and we formed a new Study Group for Contracts, SG21, with John Spicer as the chair that will continue work with even greater participation. I’m hopeful that over the coming meetings we’ll see some solid further progress in this important area.

The shape of C++20

Now that we know the final feature set of C++20, we can see this is C++’s largest release since C++11. “Major” features include:

- modules

- coroutines

- concepts including in the standard library via ranges

- <=> spaceship including in the standard library

- broad use of normal C++ for direct compile-time programming, without resorting to template metaprogramming (see last trip reports)

- ranges

- calendars and time zones

- text formatting

- span

- … and lots more …

Combined with what came in C++14 and C++17, the C++14/17/20 nine-year cycle is arguably our biggest nine-year cycle alongside the previous two (C++98 and C++11). We understand that’s exciting, but we also understand that’s a lot for the community to absorb, and so I’m also pleased that along the way we’ve done things like create the Direction Group and, most recently, SG20 on Education, to help guide and absorb continued C++ evolution in our vibrant living language.

It was not lost on the room that today was not just the day we completed the feature set of C++20, but it was also the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing. A number of people mentioned it throughout the week and especially today, some citing examples from that voyage and drawing parallels that ranged from insightful to side-splittingly funny. Here is one that I contributed after we had the vote to adopt the draft, with profuse apologies to Neil Armstrong that I couldn’t come up with something even better (sorry!):

There’s no doubt about it, C++20 is a big release with many new and important features. It’s almost done as we now enter the review and fit-and-finish phases… as we complete the work to ship the new standard over the coming two meetings, and as it then gradually becomes available for you to use in C++ implementations, we hope you will find it a useful and compelling release.

Oh, and here’s a public service announcement… even without contracts we can still make “co” jokes:

As someone pointed out to me after the session ended: This was, after all, the co_logne meeting.

Other progress and decisions

Because for the past year we’ve been focused on finishing C++20, I’ve been holding back from publishing updates to my own P0707 and P0709 proposals, generation+metaclasses and lightweight exception handling. At this meeting, I brought updates to both of those proposals again. In Study Group 7 (Compile-Time Programming) I showed an updated of P0707 and Andrew Sutton and Wyatt Childers presented updates on the Clang-based implementation progress. In the Evolution subgroup, I presented P0709 for the first time and received broad encouragement for most of the proposal along with a list of questions to which I’ll come back with answers in Belfast.

Thank you again to the approximately 220 experts who attended this meeting, and the many more who participate in standardization through their national bodies! If today our C++20 Eagle has wings, our next step is to land it, then bring it home… and so in our next two regular WG21 meetings, in November (Belfast, Northern Ireland, UK) and February (Prague, Czech Republic), we plan to respond to the C++20 international review ballot comments and make other bugfixes before sending final C++20 out for its approval ballot about seven months from now.

Have a good summer… and see many of you (and a large part of the committee) at CppCon in September!