[Updates: Clarified that an intrusive discriminator would be far beyond what most people mean by “C++ ABI break.” Mentioned unique addresses and common initial sequences. Added “unknown” state for passing to opaque functions.]

Here is my little New Year’s Week project: Trying to write a small library to enable compiler support for automatic raw union member access checking.

The problem, and what’s needed

During 2024, I started thinking: What would it take to make C/C++ union accesses type-checked? Obviously, the ideal is to change naked union types to something safe.(*) But because it will take time and effort for the world to adopt any solution that requires making source code changes, I wondered how much of the safety we might be able to get, at what overhead cost, just by recompiling existing code in a way that instruments ordinary union objects?

Note: I describe this in my C++26 Profiles proposal, P3081R0 section 3.7. The following experiment is trying to validate/invalidate the hypothesis that this can be done efficiently enough to warrant including in an ISO C++ opt-in type safety profile. Also, I’m sure this has been tried before; if you know of a recent (last 10 years?) similar attempt that measured its results, please share it in the comments.

What do we need? Obviously, an extra discriminator field to track the currently active member of each C/C++ union object. But we can’t just add a discriminator field intrusively inside each C/C++ union object, because that would change the size and layout of the object and be a massive link/ABI incompatibility even with C compilers and C code on the same platform which would all need to be identically updated at the same time, and it would break most OSes whose link compatibility (existing apps, device drivers, …) rely on C ABIs and APIs and use unions in stable interfaces; breaking that is much more than people usually mean by “C++ taking an ABI break” which is more about evolving C++ standard library types.

So we have to store it… extrinsically? … as-if in a global internally-synchronized map<void* /*union obj address*/, uintNN_t /*discriminator*/>…? But that sounds stupid scary: global thread safety lions, data locality tigers, and even some branches bears, O my! Could such extrinsic storage and additional checking possibly be efficient enough?

My little experiment

I didn’t know, so earlier this year I wrote some code to find out, and this week I cleaned it up and it’s now posted here:

The workhorse is extrinsic_storage<Data>, a fast and scalable lock-free data structure to nonintrusively store additional Data for each pointer key. It’s wait-free for nearly all operations (not just lock-free!), and I’ve never written memory_order_relaxed this often in my life. It’s designed to be cache- and prefetcher-friendly, such as using SOA to store keys separately so that default hash buckets contain 4 contiguous cache lines of keys. Here I use it for union discriminators, but it’s a general tool that could be considered for any situation where a type needs to store additional data members but can’t store them internally.

If you’re looking for a little New Year’s experiment…

If you’re looking for a little project over the next few days to start off the year, may I suggest one of these:

-

Little Project Suggestion #1: Find a bug or improvement in my little lock-free data structure! I’d be happy to learn how to make it better, fire away! Extra points for showing how to fix the bug or make it run better, such as in a PR or your cloned repo.

-

Little Project Suggestion #2: Minimally extend a C++ compiler (Clang and GCC are open source) as described below, so that every construction/access/destruction of a

uniontype injects a call to my little library’sunion_registry<>::functions which will automatically flag type-unsafe accesses. If you try this, please let me know in the comments what happens when you use the modified compiler on some real world source! I’m curious whether you find true positive union violations in theunion-violations.logfile – of course it will also contain false positives, because real code does sometimes use unions to do type punning on purpose, but you should be able to eliminate batches of those at a time by their similar text in the log file.

To make #2 easier, here’s a simple API I’ve provided as union_registry<>, which wraps the above in a compiler-intgration-targeted API. I’ll paste the comment documentation here:

// For an object U of union type that

// has a unique address, when Inject a call to this (zero-based alternative #s)

//

// U is created initialized on_set_alternative(&U,0) = the first alternative# is active

//

// U is created uninitialized on_set_alternative(&U,invalid)

//

// U.A = xxx (alt A is assigned to) on_set_alternative(&U,#A)

//

// U or U.A is passed to a function by on_set_alternative(&U,unknown)

// pointer/reference to non-const

// and we don't know the function

// is compiled in this mode

//

// U.A (alt A is otherwise used) on_get_alternative(&U,#A)

// and A is not a common initial

// sequence

//

// U is destroyed / goes out of scope on_destroy(&U)

//

// That's it. Here's an example:

// {

// union Test { int a; double b; };

// Test t = {42}; union_registry<>::on_set_alternative(&u,0);

// std::cout << t.a; union_registry<>::on_get_alternative(&u,0);

// t.b = 3.14159; union_registry<>::on_set_alternative(&u,1);

// std::cout << t.b; union_registry<>::on_get_alternative(&u,1);

// } union_registry<>::on_destroy(&u);

//

// For all unions with up to 254 alternatives, use union_registry<>

// For all unions with between 255 and 16k-2 alternatives, use union_registry<uint16_t>

// If you find a union with >16k-2 alternatives, email me the story and use union_registry<uint32_t>

Rough initial microbenchmark performance

My test environment:

- CPU: 2.60 GHz i9-13900H (14 physical cores, 20 logical cores)

- OSes: Windows 11, running MSVC natively and GCC and Clang via Fedora in WSL2

My test harness provided here:

- 14 test runs: Each successively uses { 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 32, 64, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 } threads

- Each run tests 1 million union objects, 10,000 at a time, 10 operations on each union; the test type is

union Union { char alt0; int alt1; long double alt2; }; - Each run injects 1 deliberate “type error” failure to trigger detection, which results in a line of text written to

union-violations.logthat records the bad union access including the source line that committed it (so there’s a little file I/O here too)

- Each run tests 1 million union objects, 10,000 at a time, 10 operations on each union; the test type is

- Totals:

- 14 million union objects created/destroyed

- 140 million union object accesses (10 per object, includes construct/set/get/destroy)

On my machine, here is total the run-time overhead (“total checked” time using this checking, minus “total raw” time using only ordinary raw union access), for a typical run of the whole 140M unit accesses:

| Compiler | total raw (ms) | total checked (ms) | total overhead (ms) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

MSVC 19.40 -O2 |

~190 | ~1020 | ~830 | Compared to -O2, -Ox checked was the same or very slightly slower, and -Os checked was 3x slower |

GCC 14 -O3 |

~170 | ~800 | ~630 | Compared to -O3, -O2 overall was only slightly slower |

Clang 18 -O3 |

~170 | ~510 | ~340 | Compared to -O3, -O2 checked was about 40% slower |

Dividing that by 140 million accesses, the per-access overhead is:

| Compiler | total overhead (ns) / total accesses | average overhead / access (ns) |

|---|---|---|

| MSVC | 830M ns / 140M accesses | 5.9 ns / access |

| GCC (midpoint) | 630M ns / 140M accesses | 4.5 ns / access |

| Clang | 340M ns / 140M accesses | 2.4 ns / access |

Finally, recall we’re running on a 2.6 GHhz processor = 2.6 clock cycles per ns, so in CPU clock cycles the per-access overhead is:

| Compiler | average overhead / access (cycles) |

|---|---|

| MSVC | 15 cycles / access |

| GCC | 11.7 cycles / access |

| Clang | 6.2 cycles / access |

This… seems too good to be true. I may well be making a silly error (or several) but I’ll post anyway so we can all have fun correcting them! Maybe there’s a silly bug in my code, or I moved a decimal point, or I converted units wrong, but I invite everyone to have fun pointing out the flaw(s) in my New Year’s Day code and/or math – please fire away in the comments.

Elaborating on why this seems too good to be true: Recall that one “access” means to check the global hash table to create/find/destroy the union object’s discriminator tag (using std::atomics liberally) and then also set or check either the tag (if setting or using one of the union’s members) and/or the key (if constructing or destroying the union object). But even a single L2 cache access is usually around 10-14 cycles! This would mean this microbenchmark is hitting L1 cache almost always, even while iterating over 10,000 active unions at a time, often with more hot threads than there are physical or logical cores pounding on the same global data structure, and occasionally doing a little file I/O to report violations.

Even if I didn’t make any coding/calculation errors, one explanation is that this microbenchmark has great L1 cache locality because the program isn’t doing any other work, and in a real whole program it won’t get to run hot in L1 that often – that’s a valid possibility and concern, and that’s exactly why I’m suggesting Little Project #2, above, if anyone would like to give that little project a try.

In any event, thank you all for all your interest and support for C++ and its evolution and standardization, and I wish all of you and your families a happier and more peaceful 2025!

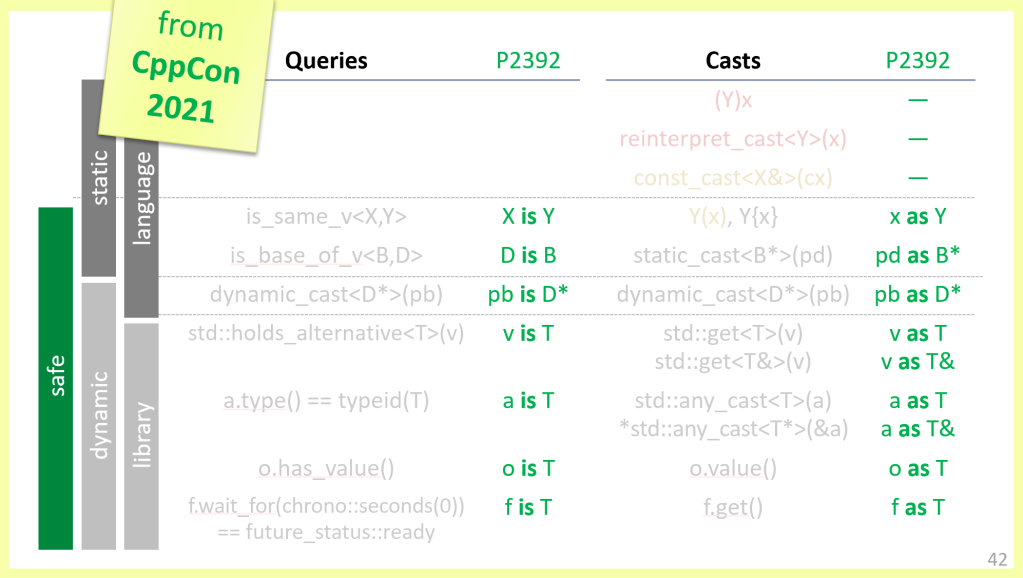

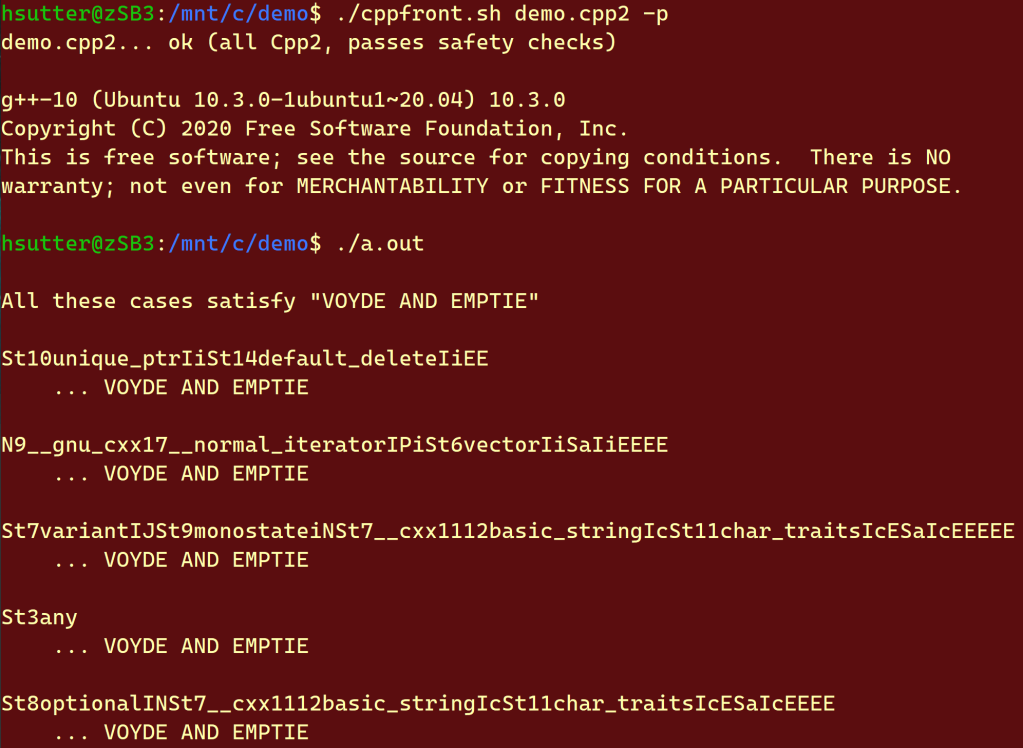

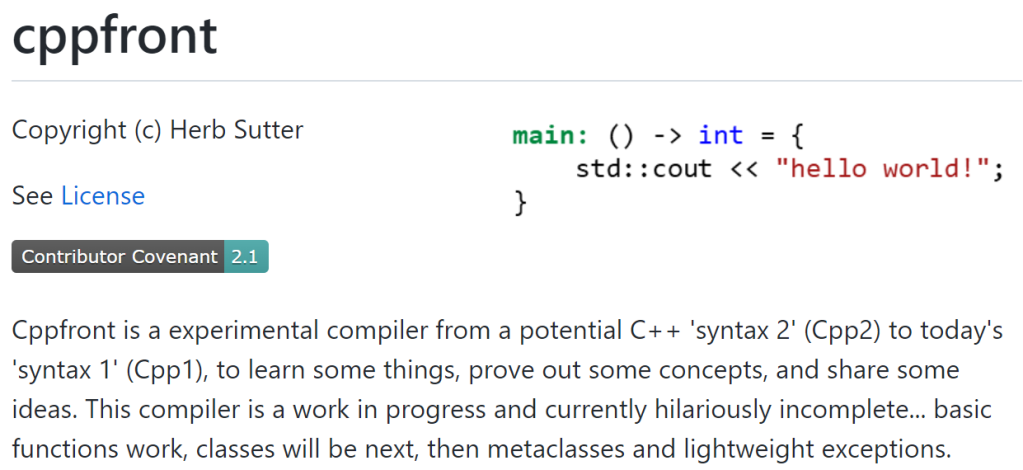

(*) Today we have std::variant which safely throws an exception if you access the wrong alternative, but variant isn’t as easy to use as union today, and not as type-safe in some ways. For example, the variant members are anonymous so you have to access them by index or by type; and every variant<int,string> in the program is also anonymous == the same type, so we can’t distinguish/overload unrelated variants that happen to have similar alternatives. I think the ideal answer – and it looks like ISO C++ is just 1-2 years from being powerful enough to do this! – will be something like the safe union metaclass using reflection that I’ve implemented in cppfront, which is as easy to use as union and as safe as variant – see my CppCon 2023 keynote starting at 39:16 for a 4-minute discussion of union vs. variant vs a safe union metafunction that uses reflection.